| О журнале | Редколлегия | Редсовет | Архив номеров | Поиск | Авторам | Рецензентам | English |

Why and how the Russian health workforce is different?

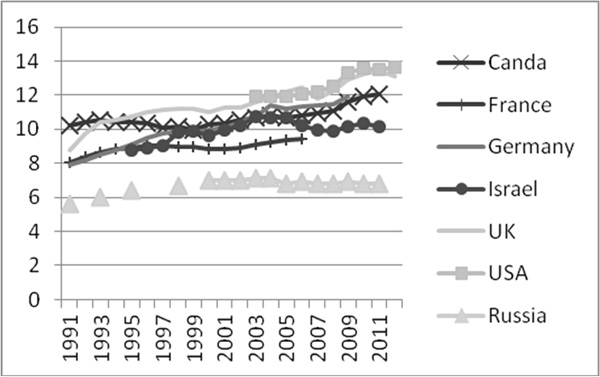

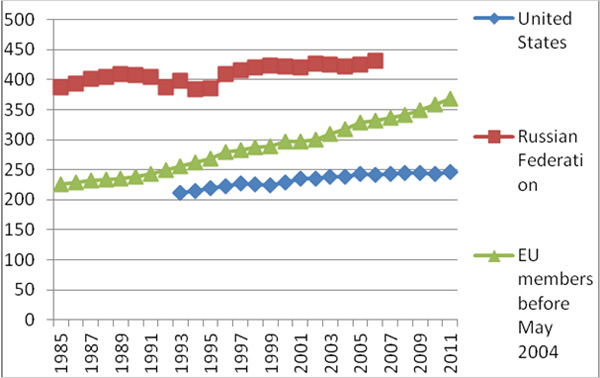

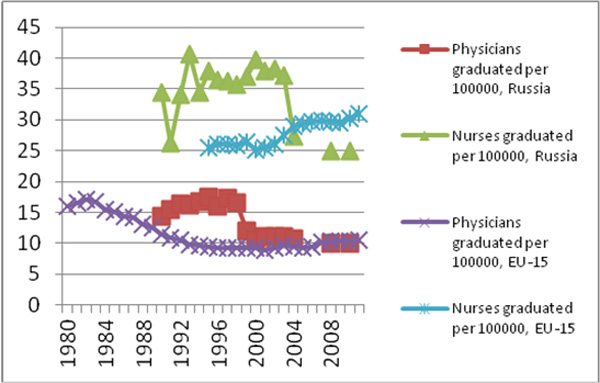

The paper uses the outcome of the research project funded from the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics Аннотация Russia underwent significant health reforms since the collapse of Soviet Union. We hypothesized that despite many changes, the Russian healthcare workforce structure remains largely unreformed and unique. This study conveys how human resources for healthcare are different in Russia compared to the most developed countries and examines the underlying reasons for these differences. Methods utilized include analysis of routine statistics and in-depth interviews with respondents who had experience as physicians and public health professionals in Russia and in the west, including physicians who emigrated from Russia and decision makers responsible for personnel policies. Results: Russian health system is traditionally viewed as vast, overstaffed, overspecialized while underfunded, however it is often overlooked that the total number of personnel employed in health care is relatively small. The relative understaffing of Russian health care results from a deficit of all categories of personnel except for physicians and nurses, as well as to misallocation of personnel. In Russia, the rates of health care workers that are neither physicians nor nurses is ca. 20 per 1000 population vs. 30-50 per 1000 in large OECD countries. In the past, an oversupply of physicians and nurses was created due to controlled enrolment in medical education. This allowed the salaries of medics to stay relatively low, while also reducing demand for allied health personnel. Since enrolment in medical colleges and schools is cut by about one third, this may lead to a need for rapid changes in personnel policies in the near future. Introduction Russia underwent significant health reforms since the collapse of Soviet Union. Reforms included the introduction of compulsory health insurance and of official payments for some types of care in state facilities [1]. The Private clinics’ role in care provision in large cities became more limited and currently represents around 6.2% of outpatient and 0.6% of inpatient care in Russia [2]. The healthcare system underwent decentralization in the 1990s, followed by partial recentralization in later years, with market forces partially replacing centralized planning [3][4]. Despite the "western orientation" of Russia, at least in the 1990s, the system still has many of the characteristics of the Soviet times and differs from the west [5]. In OECD countries significant changes in personnel structure are reported, with an increasing number of allied specialists, i.e. other than physicians and nurses, and with emerging new specialties [6]. We hypothesized that one significant area in which Russian health system remains largely unreformed and unique is the health workforce [7], including its poorly studied nature and distribution. The focus of the study was to comparethe structure of the workforce and the differences between Russia and most economically developed countries, as well as to identify the underlying reasons for these differences. Methods The OECD [8], WHO [9] and Rosstat [10] statistics on healthcare workforce numbers, rates and distribution were compared to identify recent trends and differences between Russia and the west. We have attempted to compare Russian statistics against old members of European Union (15 members that joined EU members before 2004) and USA and Canada. Whenever aggregated statistics were not available for EU, for demonstration purposes in the graphs, we use the largest European countries UK, Germany, France as comparator, adding Israel, as a country with very significant proportion of ex-Russian’s employed in health workforce. For a few indicators, data was available for USA and Canada therefore it was retrieved and included, and if longer term trends were available – then they are also included in the analysis. We have focused on total healthcare workforce, physicians, nurses as well as other categories of health workforce, and we also looked at physicians’ incomes. We then interviewed 5 graduates of medical schools in Russia who immigrated to UK (1 physician), USA (2 – one based in LA, and one in NY) and Israel (2) after some experience working as physicians in Russia. Additionally, 4 consultants with long-term experience in Russian NGOs or international agencies were contacted to assist in the analysis of differences (1 from WHO, 2 – WB, 1 – UNDP). Also, 3 former minsters and deputy ministers of health of Russia were consulted. Results Russia exhibited lower spending on health and smaller proportion of population employed in healthcare vs. OECD. While the EU public expenditure is above 8% and total spending is above 10% of the GDP, the Russian corresponding figures are 4% and 6% respectively. The private expenditure in Russia and in the EU is similar at the level of 2% of GDP. Most of OECD countries report that more than 10% of workers are employed in health and social care and the proportion is increasing. Russia is at the level of 7%, showing stability at least for the last decade (Diagram 1). Diagram 1. Proportion of working population employed in health and social care. Sources: OECD, Rosstat.  The allocation of the human resources also differs. The ratio of physicians per 1000 population in USA is 2.5, in the EU-15 just over 3 and in Russia – 4.3 (Diagram 2). The physician rates are higher in Russia than in most OECD countries, while nurses’ rates per population are very similar. The ratio of physicians to nurses therefore is 1:2 in Russia, while the indicator exceeds 1:3 in most OECD countries. The high rate of Russian physicians and the average rate of nurses in developed countries are due to high numbers of enrolment in state-run medical schools and colleges. These figures remain despite reported high rates people quitting the profession. However, the rates of graduates per population have been decreasing and are now in line with the EU for physicians and are lower for nurses (Diagram 3). Diagram 2. Rates of physicians per 100 000 population, Russia (Rosstat), EU (WHO Euro), USA (OECD), (data for Canada is unavailable).  Diagram 3. Physicians and nurses graduates per 100 000 population in the 15 old EU member countries and in Russia. Russia (Rosstat), EU (WHO Euro).  While total health workforce is smaller in Russia, the proportion of allied health workforce is also lower in Russia (Table 1). Table 1. Allied workforce statistics.

Salaries and incomes of health personnel. Physicians in OECD earn more than the mean, with only Poland and Norway in OECD reporting incomes of narrow specialists to be less than 2 times the national average, while in the USA the difference is more than 4 fold (Table 2). In Russia, official physicians’ incomes are lower, with Ministry of Health reporting a recent increase of physicians’ salaries to the level of 1.4 vs. national average, however this number is often disputed by physicians. Table 2. Salaries of physicians and rates of physicians in OECD (all countries for which data is available) and Russia. Sources: OECD, Rosstat.

The roles of professions. Physicians in Russia fulfil a lot of functions which are not typical for their counterparts in the OECD, e.g. paperwork occupying up to half of their working time (most respondents stated 45%), technical tests and device operations. A good example of such difference was brought up by a pathologist from Russia who is currently working in the USA. This participant stated that while previously working in Russia, most of the work related to post-mortem investigations, and the autopsy had to be fully performed by the doctor: "In the USA the routine manipulations are carried out by allied health workers, while only the qualified part of the work is to be undertaken by high-pay M.D. I do not cut bodies any more, I don’t even use microtome, microscope is my main tool." The nurses reported to carry out tasks such as cleaning the facilities and feeding the patients. An undersupply of a special category of "junior medical staff" tasked with cleaning, disinfection and general assistance to patients was reported. The new categories of allied health personnel which include therapists and assistants do not exist. Technicians and information specialists generally are either not defined as health workforce in Russia or their roles are fulfilled by physicians and nurses. There are difficulties employing people without medical education in healthcare facilities due to rigid organizational structures that envisage very few positions besides those of physician, nurse and junior medical staff. For instance, practically all lab staff has a medical or nursing education. Health administrators in Russia are physicians with little or no training in management, finance or public health. "With the exception of the two previous ministers of health and tiny proportion of technical specialists one requires a nursing degree or an M.D. to be employed anywhere in healthcare" – reported by a former employee of the Ministry of Health. Various forms of misallocation of health personal were also reported by 7 out of 9 respondents interviewed: these include inpatient care, paediatrics and higher paid specialties. Ineffective placement of workforce is perceived to be driven by low official salaries of the medics. Better pay in some specialties and jobs in healthcare in Russia reported to be not a result of a deliberate planning process, but rather a market driven process, while jobs and professions serving the wealthier and more desperate patients are better off. The income of the physicians in Russia consists of salary, additional bonuses, official and unofficial private payments. A complex structure of incomes of health personnel was reported to determine the career paths of the medics. Opportunities for charging official fees, for extracting informal payments, and for getting involved in activities with the medical industry which have administrative power to influence healthcare funding distribution, can allow supplementation of the official pay in certain specialties, especially in bigger cities. Discussion Before discussing the results of the study we should acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, OECD countries may not be the only comparator for Russia, however there is general tendency to use economically developed countries with better health as the benchmark. Additionally, Russia still declares intention to implement west-like healthcare forms. Secondly, the statistics availability are problematic, requiring use of different often incomplete sources. For aggregate statistics we have managed to identify sources of data and triangulated these where possible. Comparing across years should not lead to heavy biases as workforce statistics usually do not change rapidly. As for the qualitative analysis, the limitation is posed mainly by the sample size. However interviews were in-depth and related to matters obvious for those with experience of employment in healthcare in both Russia and in the west. Additionally the responses were rather uniform irrespective of their backgrounds. Russian healthcare system is traditionally viewed as vast, overstaffed, overspecialized while underfunded, however it is often overlooked that the total number of personnel employed in health is smaller when compared to the OECD. The relative understaffing is explained by the deficit of categories of personnel other than physicians and nurses, as well as the misallocation of personnel, e.g. majority of staff works in the inpatient facilities, while primary care specialists are heavily undersupplied [11]. There is also clear indication of misallocation of staff towards specialties that allow better incomes. Hence Russian healthcare seems not only underfunded with 3.8% GDP public spending on health, but also understaffed with 6.8% of workers employed by health and social sector vs. over 10% and growing in OECD. While rates of physicians are high in Russia this leads to relatively low nurses to physician ratio. These are 2:1 compared to 2:3-2:4 in most OECD countries. The nurse to doctor ratio is lower than that in the developed countries due to high rates of physicians to population, while nurses are at the EU average. Russian nurses fulfil many roles of assistants, therapists and other allied health staff in the western world, therefore it is likely that in reality there is deficit of nursing care compared to the west even with similar quantities of nurses. Definitions of allied health professions vary across countries and contexts, with the term not yet widely used in Russia. Ca. 60% of health and social care workforce in Russia is neither physicians nor nurses, leading to rates of ca. 20 per 1000 population vs. 30-50 per 1000 in large OECD countries of comparison. Hence there are ca. 1.5-2 times less allied health workers per population in Russia compared to the OECD. It seems that the salaries level largely determine roles and rates of personnel. Russia is the country with one of the highest supply of physicians in the world. Russia has almost as many physicians as the USA with only half the population. The policy makers interviewed confirmed our hypothesis that low salaries of physicians are among the factors leading to low demand for substituting them by lower cost personnel, such as nurses or allied health specialists. We argue that while most countries with underfunded healthcare cannot afford high numbers of doctors, Russia in the past has been able to maintain their low-cost through exclusive control over medical education with all physicians still trained in state universities. Creating an oversupply of physicians and nurses allowed for keeping the salaries relatively low, while there is obviously a degree of quitting the profession as well as issues of qualifications, morale and of informal payments [12]. The Informal sector rooted in the soviet times compensates medical personnel incomes, recently partially substituted by official payments [13]. This led to physicians fulfilling types of roles not typical in other countries, which are often shifted to nurses and allied health workers. Physicians are still considered to be key personnel in any health system; however in Russia they run the system even to a greater extent than elsewhere. Practically all health administrators are MDs. Physicians perform activities typically assigned to technicians, information specialists, therapists, paramedics and nurses in the OECD. Given the decline of supply of medics indicated, however, the workforce situation can be expected to change in the near future. Key words health care system, medical personnel, medical specialty, personnel structure, wage-rates References 1. Balabanova DC, Falkingham J, McKee M. Winners and losers: expansion of insurance coverage in Russia in the 1990s Am J Public Health. 2003 Dec;93(12):2124-30 2. S. Shishkin. С.В.Шишкин Роль частных медицинских организаций в российской системе здравоохранения. http://regconf.hse.ru/uploads/a998908f8075c0909f8d7cf796d568ac39326008.docx. 3. Danishevski K, Balabanova D, McKee M, Atkinson S. The fragmentary federation: experiences with the decentralized health system in Russia. Health Policy Plan. 2006 May; 21 (3):183-94. 4. Shishkin S. http://opec.ru/1346971.html 5. Sheaff R. Governance in gridlock in the Russian health system; the case of Sverdlovsk oblast. Soc Sci Med. 2005 May; 60(10):2359-69. 6. AAHSP (2012) "Association of Allied Health Schools, Definition of Allied Health Professionals". 2012 Asahp.org 7. Rechel, B.; Dubois, C.-A.; McKee, M. The health care workforce in Europe. Learning from experience. WHO Regional Office for Europe (Copenhagen) 2006. 8. http://stats.oecd.org/ 9. http://www.euro.who.int/en/data-and-evidence/databases/european-health-for-all-database-hfa-db 10. http://www.gks.ru/ 11. Rese A, Balabanova D, Danishevski K, McKee M, Sheaff R. Implementing general practice in Russia: getting beyond the first steps. BMJ. 2005 Jul 23;331(7510):204-7 12. Gordeev VS, Pavlova M, Groot W. Informal payments for health care services in Russia: old issue in new realities. Health Econ Policy Law. 2013 May 21:1-24 13. Ensor, T. (2004). Informal payments for health care in transition economies. Social Science & Medicine, 58 (2), 237-246. |

[ См. также ] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Журнал «Медицина» © ООО "Инновационные социальные проекты"

|